In the end, isn't all of this working to establish systems of language that we feel most accurately account for the state of things ethical.

That is, we want to know how to live. So we do live, some of us, ironically enough, lives of leisure concentrated on finding out how best to live. And to be honest, most minutes of the day I wouldn't want it otherwise. Occasionally, dailily, a panic will descend on me, saying, Justin! Why aren't you working your fingers to the bone!

I answer him with silence. I have no reason, except for a soft conviction concerning the value of work: quality and not quantity. Working to the bone and working well are not mutually exclusive, but it's easy enough to let them be.

Science! Funny when you think of it. I suppose it's contribution to the control we humans have over nature has provided me with my leisure, and yet... Mightn't I be just as happy in a medieval world, and act just as ethically? I might, yes, as self-righteous and naive as the question sounds. Montaigne, in his aristocratic leisure, sitting at home, translating, with more than a twinge of Irony, the work of Raymond Sebold...

Ethics: acting in a way that elicits confidence in and love for your person from the most people.

Knowledge (n.): The relationship between yourself and the world. Some call this our mental and physical impressions of the world's information. Also, the mental and physical categories we make for this information -- distinctions and organizations that continue to produce the capacity for more knowing.

To Know (v.): to develop a relationship between yourself and the world. (Also, the categorizing of impressions gathered during this relationship)

Belief: To be convinced of the relative accuracy or usefulness of some part of your worldly impressions.

Certainty: To be overly convinced of such.

It's all in Montaigne. Who got it all from Plutarch. Who got it all from ... Heraclitus? We've harped on this same chord for more than 2,000 years and yet...

Someone might say that without curiosity, we would wither away. But curiosity implies a light-hearted pursuit of knowledge. One that opens the eyes softly, rather than one that eats at the gut. An enlightenment, rather than an emburdenment, an embitterment, which always follows a perceived empowerment.

Adam and Eve ate from the fruit rather than naming the animals, both of which were kinds of knowing.

Which brings me to Human Dogma. The wonderful thing about complete skepticism and nihilism is that none of us are convinced by them. There are a few impressions, which we believe we've managed to communicate to each other, that we are all completely convinced of the accuracy of. I've named them before in this blog, but again: 1. That we have a self. 2. That it exists in a world (implying a web of things, given boundaries by and categorized according to their meaning in our lives). 3. That there are other selves.

And if its true that we share some basic beliefs, and that all other beliefs are made of impressions whose accurate naming we merely make ourselves feel convinced of -- well, before I finish that sentence, I suppose I should stop and consider that this idea would be impressed upon others and elicit conviction its accuracy only with great difficulty -- i.e. by being very convincing. I.e. rhetoric.

The role rhetoric plays in a world of seeming is indivisible from the role knowing plays -- what we know, we know by conviction. What has convinced us of what we know? Do you know you are sitting at your computer? How? Because you believe your senses, which are a power you believe in due to your capacity to categorize impressions, which is a power you believe in. Which isn't to say anything about belief in the statement "You are sitting at your computer." But we believe in our power of making useful phonemes and morphemes the same way -- we are convinced by certain impressions.

Try to convince me that Abraham Lincoln lived. You can't do it completely. If someone brought to me what I considered overwhelming evidence that Lincoln was a hoax perpetrated by the Illuminati, I would likely believe him. Especially if others started to hold that idea as accurate.

But try to convince me I don't exist, and gol-dernit, I won't quit.

Perhaps after some pretty extensive brainwashing, but I'm fairly certain it wouldn't stick. I'd stop eating and talking, to adhere to my new conviction, and then... I'd get hungry... and I'd ask for food...

Try to convince me you don't exist, and I'll only believe in your existence more.

So, what do we call it when people act on kill each other over impressions/idea/conceptions that neither party are fully convinced of (relative to the Human Dogma)? What else, but foolishness?

Sitting pretty in my ivory tower. Come down, come down, little fool.

Thursday, July 31, 2008

An excerpt

Throughout this long development, from 600 B.C. to the present day, philosophers have been divided into those who wished to tighten social bonds and those who wished to relax them. With this difference others have been associated. The disciplinarians have advocated some system of dogma, either old or new, and have therefore been compelled to be in a greater or less degree, hostile to science, since their dogmas could not be proved empirically. They have almost invariably taught that happiness is not the good, but that "nobility" or "heroism" is to be preferred. They have had a sympathy with the irrational parts of human nature, since they have felt reason to be inimical to social cohesion. The libertarians, on the other hand, with the exception of the extreme anarchists [Robespierre!], have tended to be scientific, utilitarian, rationalistic, hostile to violent passion, and enemies of all the more profound forms of religion. This conflict existed in Greece before the rise of what we recognize as philosophy, and is already quite explicit in the earliest Greek thought. In changing forms, it has persisted down to the present day, and no doubt will persist for many ages to come.

[Well, at least we've established a bias, Mr. Russell]

[Well, at least we've established a bias, Mr. Russell]

The Rise of Greek Civilization

So, Russell left us last week with an oscillation -- the pitch between social-cohesion/tradition/authority/dogma and individualism/empiricism/science.

Which makes me think of Galileo, sitting before the Catholic tribunal, feeling convinced of what he had observed and reasoned, and yet perhaps also feeling sympathy for the concepts that the Catholic Church had draped her authority, and therefore her empire, over.

Perhaps the best image of this oscillation is the French Revolution. France swung, in a matter of ten years, from a Monarchical society, where Aristocracy and Clergy held places of power, to "forms based on the Enlightenment" -- individualism, science, democracy. Many hold that the conflict came because of the clash between the capitalistic bourgeoisie and the aristocracy -- which sounds again like this oscillation.

Russell chooses, I think, a middle way. He is all for science and subjectivity, but he also knows that Storming the Bastille might mean you get, along with a Republic, The Reign of Terror. You might get blood-thirsty mobs running through the streets.

Which makes me respect the original United States Government all the more -- for striking a delicate balance, or seeming to at least, between centralized power and individual freedom. But then, I have libertarian leanings.

Money -- so much has been said about it -- symbol of individualism, issued by a centralized power.

Which has nothing yet to do with the Rise of Greek Civilization.

Which makes me think of Galileo, sitting before the Catholic tribunal, feeling convinced of what he had observed and reasoned, and yet perhaps also feeling sympathy for the concepts that the Catholic Church had draped her authority, and therefore her empire, over.

Perhaps the best image of this oscillation is the French Revolution. France swung, in a matter of ten years, from a Monarchical society, where Aristocracy and Clergy held places of power, to "forms based on the Enlightenment" -- individualism, science, democracy. Many hold that the conflict came because of the clash between the capitalistic bourgeoisie and the aristocracy -- which sounds again like this oscillation.

Russell chooses, I think, a middle way. He is all for science and subjectivity, but he also knows that Storming the Bastille might mean you get, along with a Republic, The Reign of Terror. You might get blood-thirsty mobs running through the streets.

Which makes me respect the original United States Government all the more -- for striking a delicate balance, or seeming to at least, between centralized power and individual freedom. But then, I have libertarian leanings.

Money -- so much has been said about it -- symbol of individualism, issued by a centralized power.

Which has nothing yet to do with the Rise of Greek Civilization.

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

Blue Angel

written at Squaw...

My brother chose Bubba Shot the Jukebox

For God knows why. He bought some snakeskin boots.

This was our brief Summer of Country, and

I did it my way: more secretive, no

Tight jeans, no cowboy hat – I hadn’t yet rung

Puberty’s bell. I still crept through starless vaults

Rat-like, even as we learned to line-dance,

Both hands hooked on bighorn buckles – Angel

It was then I chose you. That night

The newly buxom white-fringed girls

bootscooted the hardwood, invisible to me.

A lonely tune began to conjure you

from another, darker, world. Blue Angel, he crooned,

And my rat-eyes gleamed, and my brother, dimly, knew.

My brother chose Bubba Shot the Jukebox

For God knows why. He bought some snakeskin boots.

This was our brief Summer of Country, and

I did it my way: more secretive, no

Tight jeans, no cowboy hat – I hadn’t yet rung

Puberty’s bell. I still crept through starless vaults

Rat-like, even as we learned to line-dance,

Both hands hooked on bighorn buckles – Angel

It was then I chose you. That night

The newly buxom white-fringed girls

bootscooted the hardwood, invisible to me.

A lonely tune began to conjure you

from another, darker, world. Blue Angel, he crooned,

And my rat-eyes gleamed, and my brother, dimly, knew.

One more post from Richardson

This collection also has aphorisms! I love this guy. Here are some that caught my eye as I flipped through them:

219. It takes more than one life to be sure what's killing you.

221. More than you remember stays green all winter.

222. Worry wishes life were over.

224. Water deepens where it has to wait.

227. I am saving good deeds to buy a great sin.

234. Why should the whole lake have the same name?

242. If I can keep giving you want you want, I may not have to love you.

395. Disillusionment is also an illusion.

475. We have secrets from others. But our secrets have secrets from us.

32. If you're Larkin or Bishop, one book a decade is enough. If you're not? More than enough.

39. The will is weak. Good thing, or we'd succeed in governing our lives with our stupid ideas!

128. Intimates: the ones it's hardest to tell everything you're thinking.

212. Happiness is not the only happiness.

276. No gardens without weeds? No weeds without gardens.

219. It takes more than one life to be sure what's killing you.

221. More than you remember stays green all winter.

222. Worry wishes life were over.

224. Water deepens where it has to wait.

227. I am saving good deeds to buy a great sin.

234. Why should the whole lake have the same name?

242. If I can keep giving you want you want, I may not have to love you.

395. Disillusionment is also an illusion.

475. We have secrets from others. But our secrets have secrets from us.

32. If you're Larkin or Bishop, one book a decade is enough. If you're not? More than enough.

39. The will is weak. Good thing, or we'd succeed in governing our lives with our stupid ideas!

128. Intimates: the ones it's hardest to tell everything you're thinking.

212. Happiness is not the only happiness.

276. No gardens without weeds? No weeds without gardens.

Encyclopedia of Stones

(These are entries from James Richardson's Encyclopedia of the Stones - a Pastoral.)

1.

They do not believe in the transmigration of souls.

They say their bodies will move

as leaves through light.

Everything would be perfect if the atoms

were the right shape and did not fall down.

2.

They resent being inscribed

as if they could not remember,

but they congratulate us on the wisdom

of using them to mark graves.

3.

Sand makes them nervous.

4.

They perceive the cosmos as the interior

of a mighty stone.

At night this is perfectly clear.

5.

Long ago

they began to give of their light

to build what we now call the moon.

It was almost finished.

6.

Tradition says they were the paperweights of a lord

whose messages rotted beneath them.

So they think hard.

The old remember being flowers,

but the young ridicule them and remember fire.

8.

This is their heroic myth:

"One afternoon the great stone set out."

It is not over.

9.

They are unable to perceive moths.

10.

They have a dream, but it is taking

all of them all time

to imagine it.

13.

Knowing them to be fond of games, I asked

why they did not arrange themselves

according to the constellations, but they said

Look.

22.

Here is another one of their stories:

"One Stone."

Like the others it is characterized

by control of plot and fidelity to the real.

24.

They are experimenting with sex

but are still waiting for the first ones to finish.

28.

When it is unbearably clear,

the stones have taken a deep breath.

35.

When I describe to them how we see a shooting star,

they say "That is how you look to us."

When I tell them how they look to me,

they are elated and describe in turn

something I have never seen and do not understand.

37.

Some of their favorites: October,

salt, flowers, 10 P.M., starfish,

Paul Klee, stories, waiting, the moon.

38.

You know the sky is blue

from the accumulated breath of stones,

or will, next time you are asked.

48.

I told them my favorite story:

"One day."

They liked it except for

the surprise ending.

49.

They know the infinitesimal ways

to the center of peach and oyster,

cherry, brain and heart.

63.

I say "How do you get to the river?"

They say "It will come."

1.

They do not believe in the transmigration of souls.

They say their bodies will move

as leaves through light.

Everything would be perfect if the atoms

were the right shape and did not fall down.

2.

They resent being inscribed

as if they could not remember,

but they congratulate us on the wisdom

of using them to mark graves.

3.

Sand makes them nervous.

4.

They perceive the cosmos as the interior

of a mighty stone.

At night this is perfectly clear.

5.

Long ago

they began to give of their light

to build what we now call the moon.

It was almost finished.

6.

Tradition says they were the paperweights of a lord

whose messages rotted beneath them.

So they think hard.

The old remember being flowers,

but the young ridicule them and remember fire.

8.

This is their heroic myth:

"One afternoon the great stone set out."

It is not over.

9.

They are unable to perceive moths.

10.

They have a dream, but it is taking

all of them all time

to imagine it.

13.

Knowing them to be fond of games, I asked

why they did not arrange themselves

according to the constellations, but they said

Look.

22.

Here is another one of their stories:

"One Stone."

Like the others it is characterized

by control of plot and fidelity to the real.

24.

They are experimenting with sex

but are still waiting for the first ones to finish.

28.

When it is unbearably clear,

the stones have taken a deep breath.

35.

When I describe to them how we see a shooting star,

they say "That is how you look to us."

When I tell them how they look to me,

they are elated and describe in turn

something I have never seen and do not understand.

37.

Some of their favorites: October,

salt, flowers, 10 P.M., starfish,

Paul Klee, stories, waiting, the moon.

38.

You know the sky is blue

from the accumulated breath of stones,

or will, next time you are asked.

48.

I told them my favorite story:

"One day."

They liked it except for

the surprise ending.

49.

They know the infinitesimal ways

to the center of peach and oyster,

cherry, brain and heart.

63.

I say "How do you get to the river?"

They say "It will come."

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Squaw Valley, James Richardson, and Russell

I've been a week away, and so Russell has had to wait by the wayside. Whatever that might mean. I've been in Squaw Valley, which is a lovely dip in the rock, a meadow lined with Aspens, twenty minutes away from Tahoe. I was there for a writing conference, and did write, some of which I will shortly post.

Today I've been catching up on the centuries -- that is, regaining the speed necessary to not be flung far off when I lay a hand back to Russell. Charting the 15th. If the 16th century was the beginning of the modern era, then the 15th was the ending of the middle era, the middle ages -- Constantinople fell, Brunelleschi painted perspective, Gutenberg invented the Press, and Columbus sailed the Ocean Blue.

And I've also been reading James Richardson's poetry -- suggested to me by Jim McMichael, who is my professor here at UCI, and was a nominee for 2006's National Book Award.

It's a collection called Interglacial. The first three poems -- one which serves as an epigraph, and two from his first collection called Reservations -- are fantastic. They don't give me the feeling of beings rhetorical tricks, which of course merely means they are better at being rhetorical, at convincing me -- more convincingly speaking of some True.

Here is one of his published in the New Yorker (I like it):

End of Summer

Just an uncommon lull in the traffic

so you hear some guy in an apron, sleeves rolled up,

with his brusque sweep brusque sweep of the sidewalk,

and the slap shut of a too thin rental van,

and I told him no a gust has snatched from a conversation

and brought to you, loud.

It would be so different

if any of these were missing is the feeling

you always have on the first day of autumn,

no, the first day you think of autumn, when somehow

the sun singling out high windows,

a waiter settling a billow of white cloth

with glasses and silver, and the sparrows

shattering to nowhere are the Summer

waving that here is where it turns

and will no longer be walking with you,

traveller, who now leave all of this behind,

carrying only what it has made of you.

Already the crowds seem darker and more hurried

and the slang grows stranger and stranger,

and you do not understand what you love,

yet here, rounding a corner in mild sunset,

is the world again, wide-eyed as a child

holding up a toy even you can fix.

How light your step

down the narrowing avenue to the cross streets,

October, small November, barely legible December.

Today I've been catching up on the centuries -- that is, regaining the speed necessary to not be flung far off when I lay a hand back to Russell. Charting the 15th. If the 16th century was the beginning of the modern era, then the 15th was the ending of the middle era, the middle ages -- Constantinople fell, Brunelleschi painted perspective, Gutenberg invented the Press, and Columbus sailed the Ocean Blue.

And I've also been reading James Richardson's poetry -- suggested to me by Jim McMichael, who is my professor here at UCI, and was a nominee for 2006's National Book Award.

It's a collection called Interglacial. The first three poems -- one which serves as an epigraph, and two from his first collection called Reservations -- are fantastic. They don't give me the feeling of beings rhetorical tricks, which of course merely means they are better at being rhetorical, at convincing me -- more convincingly speaking of some True.

Here is one of his published in the New Yorker (I like it):

End of Summer

Just an uncommon lull in the traffic

so you hear some guy in an apron, sleeves rolled up,

with his brusque sweep brusque sweep of the sidewalk,

and the slap shut of a too thin rental van,

and I told him no a gust has snatched from a conversation

and brought to you, loud.

It would be so different

if any of these were missing is the feeling

you always have on the first day of autumn,

no, the first day you think of autumn, when somehow

the sun singling out high windows,

a waiter settling a billow of white cloth

with glasses and silver, and the sparrows

shattering to nowhere are the Summer

waving that here is where it turns

and will no longer be walking with you,

traveller, who now leave all of this behind,

carrying only what it has made of you.

Already the crowds seem darker and more hurried

and the slang grows stranger and stranger,

and you do not understand what you love,

yet here, rounding a corner in mild sunset,

is the world again, wide-eyed as a child

holding up a toy even you can fix.

How light your step

down the narrowing avenue to the cross streets,

October, small November, barely legible December.

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Introduction to Russell's "History"

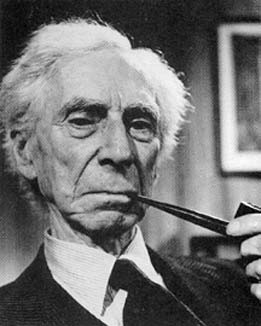

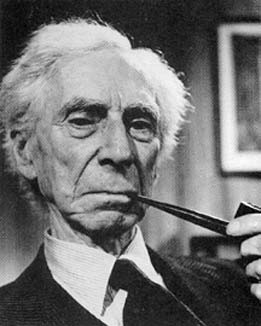

I was taught to consider "evil" all those who spoke out against the tradition in which I was raised. To look on them with a mixture of pity and hate.

I found Russell's "Why I am not a Christian" when I was in high-school, and promptly assigned him to my growing blacklist. I found his arguments to be outrageous. I decided, almost immediately, that they were juvenile, inflammatory, and empty.

Of course, they aren't. They are, for the most part, compelling. They do still prickle my skin, simply by being polemics aimed at the heart of my mind -- however, he himself has since been granted (by whom?) a pardon. His horns have fallen off. I've read a bit of a biography of his childhood as well as bits of other works, and they've convinced me of his sincere desire to believe what he feels are honest and justifiable things to believe.

"Why I'm not a Christian" ends by advocating the leaving-off of dogmas -- "A good world needs knowledge, kindliness, and courage; it does not need a regretful hankering after the past or a fettering of the free intelligence by the words uttered long ago by ignorant men," Russell says.

20 years later, in the middle of the second world war, Russell finished writing his History of Western Philosophy, with the help of his wife Patricia (who did most of the research for him). The issue of dogma factors heavily in this work as well. Dogma is on one end of the pendulum swing that Western Philosophy has been beating out since the beginning -- the other is Science. The No Man's Land between the two is Philosophy -- "something intermediate between Theology and Science."

All definite knowledge ... belongs to Science; all dogma as to what surpasses definite knowledge belongs to Theology. ... Almost all the questions of most interest to speculative minds are sych as science cannot answer, and the confident answers of theologians no longer seem so convincing as they did in former centuries.

He lists a series of unanswerable questions, questions that require dogmatic belief, or ... philosophy. He asserts that this book will be the answer to the question of why, historically, philosophy has bothered to ponder these unanswerable questions. Action depends on belief, and to understand why people acted the way they did, is to understand, in part, what they believed.

Science tells us what we can know -- not much -- and Theology purports to fill in the rest. Russell clearly doesn't appreciate this gesture. He would rather live bravely through the uncertainty he believes himself to be in, but "it is not good either to forget the questions that philosophy asks..."

To teach how to live without certainty, and yet without being paralyzed by hesitation, is perhaps the chief thing that philosophy, in our age, can still do for those who study it.

Russell then proceeds to give us the brief outline of history, through this oscillation-lens. He links to dogma any sort of cultural tradition that unites a people in a unified belief -- thus creating civilization of some sort -- and to science he ties any individualism or free-minded exploration of the world that tends to dissolve societal bonds. The cycle of history, according to Russell, follows this track, back and forth, rigid tradition to a relaxation to the beginnings of free-minded genius, to dissolution, to tyranny, whereby a new tradition is instituted ...

Russell ends his introduction with a rally-cry quite similar to that of "Why I am not..." His vision of a brighter future, in this instance, comes under the title of "Liberalism":

The doctrine of liberalism is the attempt to escape this endless oscillation [the one I've illustrated for you above.] The essence of liberalism is an attempt to secure a social order not based on irrational dogma, and insuring stability without innvolving more restraints than are necessary for the preservation of the community. Whether this attempt can succeed...

...only the future can determine.

I found Russell's "Why I am not a Christian" when I was in high-school, and promptly assigned him to my growing blacklist. I found his arguments to be outrageous. I decided, almost immediately, that they were juvenile, inflammatory, and empty.

Of course, they aren't. They are, for the most part, compelling. They do still prickle my skin, simply by being polemics aimed at the heart of my mind -- however, he himself has since been granted (by whom?) a pardon. His horns have fallen off. I've read a bit of a biography of his childhood as well as bits of other works, and they've convinced me of his sincere desire to believe what he feels are honest and justifiable things to believe.

"Why I'm not a Christian" ends by advocating the leaving-off of dogmas -- "A good world needs knowledge, kindliness, and courage; it does not need a regretful hankering after the past or a fettering of the free intelligence by the words uttered long ago by ignorant men," Russell says.

20 years later, in the middle of the second world war, Russell finished writing his History of Western Philosophy, with the help of his wife Patricia (who did most of the research for him). The issue of dogma factors heavily in this work as well. Dogma is on one end of the pendulum swing that Western Philosophy has been beating out since the beginning -- the other is Science. The No Man's Land between the two is Philosophy -- "something intermediate between Theology and Science."

All definite knowledge ... belongs to Science; all dogma as to what surpasses definite knowledge belongs to Theology. ... Almost all the questions of most interest to speculative minds are sych as science cannot answer, and the confident answers of theologians no longer seem so convincing as they did in former centuries.

He lists a series of unanswerable questions, questions that require dogmatic belief, or ... philosophy. He asserts that this book will be the answer to the question of why, historically, philosophy has bothered to ponder these unanswerable questions. Action depends on belief, and to understand why people acted the way they did, is to understand, in part, what they believed.

Science tells us what we can know -- not much -- and Theology purports to fill in the rest. Russell clearly doesn't appreciate this gesture. He would rather live bravely through the uncertainty he believes himself to be in, but "it is not good either to forget the questions that philosophy asks..."

To teach how to live without certainty, and yet without being paralyzed by hesitation, is perhaps the chief thing that philosophy, in our age, can still do for those who study it.

Russell then proceeds to give us the brief outline of history, through this oscillation-lens. He links to dogma any sort of cultural tradition that unites a people in a unified belief -- thus creating civilization of some sort -- and to science he ties any individualism or free-minded exploration of the world that tends to dissolve societal bonds. The cycle of history, according to Russell, follows this track, back and forth, rigid tradition to a relaxation to the beginnings of free-minded genius, to dissolution, to tyranny, whereby a new tradition is instituted ...

Russell ends his introduction with a rally-cry quite similar to that of "Why I am not..." His vision of a brighter future, in this instance, comes under the title of "Liberalism":

The doctrine of liberalism is the attempt to escape this endless oscillation [the one I've illustrated for you above.] The essence of liberalism is an attempt to secure a social order not based on irrational dogma, and insuring stability without innvolving more restraints than are necessary for the preservation of the community. Whether this attempt can succeed...

...only the future can determine.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

One of a Kinds

The ones

who each think

that they are the one

not of, but distinct

from the kind.

They are right --

for the kind know

it's wrong to seem

to themselves as anything

but the one who is

very much like

every other.

To say "I like you"

is to make this claim.

who each think

that they are the one

not of, but distinct

from the kind.

They are right --

for the kind know

it's wrong to seem

to themselves as anything

but the one who is

very much like

every other.

To say "I like you"

is to make this claim.

Friday, July 11, 2008

"Thoughts that are at peace"

When you find yourself awake at 1 am charting the events of the 16th century, you should ask yourself: Am I insane? Am I doing this out of anxiety, or pride, or because of strange love?

I'll agree with Wittgenstein, who was in turn agreeing with a great many philosophers before him, starting with Socrates, who first said: The goal of philosophy is thoughts that are at peace.

That is, the product of loving wisdom is thoughts that are at peace. Wisdom is -- so the cliche goes -- knowing that you don't know much. Loving wisdom -- that is: humbly observing and meditating on the world and its ways because you just want to, that is: philosophy -- is the process of untangling what you think you know and why you think you know it. It is therapeutic. It is freeing oneself, and humbling oneself, at the same time.

Knowledge is what we call our belief concerning the experiential relationship between ourselves and the world. It is a relationship. Certainty is the name of a feeling we have about that relationship. It is not the result of mathematical deduction. One becomes more or less convinced that what one says about the relationship between oneself and the world is an accurate way of saying it.

I for one am glad for the few simple human dogmas we all, or nearly all, share: 1. That we are existing in a world (I've never met or heard of someone not considered crazy who did not act on this belief) (if you say "Buddhism" I say read the story of Siddhartha's enlightenment, and think on the significance of the way he comes to it) (If you say George Berkeley, I say that saying that the world is actually there or saying that it is just perceived aren't really different, practically speaking) 2. That the world, existing outside of us, is governed by laws that we perceive, not that we create. 3. That reflecting on and talking about our relationship to the world, revering the existence of and power of objective reality, is a good thing: Sursum Corda -- lift up your heart.

To that end, some stay up late charting the centuries, mulling over the course of human thought and action. We are strange creatures -- strange that it fills me with feelings of wonder and of its strangeness -- strange compared to what?

I think it is strange compared to what I once thought of being human. Which wasn't much -- not much thinking, that is. Or, thinking that happened behind many veils.

So, to get to my purpose: I am reading Betrand Russell's "History of Western Philosophy" and will be doing little summaries of the chapters here, for my own benefit. I have an awful memory. Fixing this online, forever!, will be helpful for me, and maybe also for anyone else who happens to stumble upon it, and doesn't have the time to read the actual 800 page text.

I'll agree with Wittgenstein, who was in turn agreeing with a great many philosophers before him, starting with Socrates, who first said: The goal of philosophy is thoughts that are at peace.

That is, the product of loving wisdom is thoughts that are at peace. Wisdom is -- so the cliche goes -- knowing that you don't know much. Loving wisdom -- that is: humbly observing and meditating on the world and its ways because you just want to, that is: philosophy -- is the process of untangling what you think you know and why you think you know it. It is therapeutic. It is freeing oneself, and humbling oneself, at the same time.

Knowledge is what we call our belief concerning the experiential relationship between ourselves and the world. It is a relationship. Certainty is the name of a feeling we have about that relationship. It is not the result of mathematical deduction. One becomes more or less convinced that what one says about the relationship between oneself and the world is an accurate way of saying it.

I for one am glad for the few simple human dogmas we all, or nearly all, share: 1. That we are existing in a world (I've never met or heard of someone not considered crazy who did not act on this belief) (if you say "Buddhism" I say read the story of Siddhartha's enlightenment, and think on the significance of the way he comes to it) (If you say George Berkeley, I say that saying that the world is actually there or saying that it is just perceived aren't really different, practically speaking) 2. That the world, existing outside of us, is governed by laws that we perceive, not that we create. 3. That reflecting on and talking about our relationship to the world, revering the existence of and power of objective reality, is a good thing: Sursum Corda -- lift up your heart.

To that end, some stay up late charting the centuries, mulling over the course of human thought and action. We are strange creatures -- strange that it fills me with feelings of wonder and of its strangeness -- strange compared to what?

I think it is strange compared to what I once thought of being human. Which wasn't much -- not much thinking, that is. Or, thinking that happened behind many veils.

So, to get to my purpose: I am reading Betrand Russell's "History of Western Philosophy" and will be doing little summaries of the chapters here, for my own benefit. I have an awful memory. Fixing this online, forever!, will be helpful for me, and maybe also for anyone else who happens to stumble upon it, and doesn't have the time to read the actual 800 page text.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)